Last week, I covered the common misconceptions around trauma, some of the clinical pitfalls, and the importance of having realistic expectations when helping someone with non-epileptic seizures. In this final part of the series, I turn to formulation, the importance of structure as part of the roadmap, and some practical techniques.

How can psychology help?

Psychotherapy has been embedded in physical health settings for decades, including rehabilitation after stroke and brain injury, management of chronic pain, condition management for diabetes, and as an adjunct treatment alongside chemotherapy in oncology services.

Of course, it would be implausible to suggest that psychotherapy alone can cure or fix physical health problems. Still, there is good evidence that it can help with the experience of illness and improve health outcomes.

What is formulation?

I think of formulation as a working map that we continuously revise and update. We pin down what is happening in the here and now, the potential roads that may have led up to this point, and the possible directions the person can take.

Yet, balancing the pull of traditional psychotherapy models with practical health management strategies has possibly been my biggest learning curve working with FND. Exploring the past is necessary, but it should not overshadow the primary focus of therapy.

In almost every case, the person’s main reason for referral is to reduce and improve the seizures they experience in the present. Most wouldn’t be in the room otherwise.

Why does history matter?

This is a frequent question, especially if someone has no history of mental health problems and the seizures have seemingly started out of the blue. Essentially, it helps us understand possible factors that shaped a person’s emotional management.

Common strategies are formed during early life and include: separating things into good vs bad, people pleasing, compliance, smiling, or separating thoughts from feelings. This isn’t necessarily a problem in itself, unless it’s negatively impacting your life, or it no longer works and your body has started doing some funky stuff as a result.

Obviously, managing unpleasant feelings is part of daily life, and many people spend years avoiding them. Anyone who experiences chronic anxiety or mood-based problems will likely do this to some degree. I certainly have.

Intolerance of strong emotions such as rage and guilt is very common, and is possibly the most frequent that I encounter with dissociative seizures.

Once non-epileptic attacks begin, the person’s prior management strategies tend to be bypassed. When emotions build, the body protects itself by shutting down awareness altogether. At the risk of making this sound a tad “scientific,” therapy aims to help the thinking and emotional parts of the brain communicate a bit better.

Naturally, if you're flat-out on the floor when strong emotions rise because you don't notice them in advance, it can create significant difficulty for exposure-based therapy.

What does formulation look like in practice?

There are lots of ways to formulate, depending on the type of therapy you are doing. I tend to take an integrative approach. As with any psychological problem, particularly when working with overlapping and complex conditions, simplicity and shared understanding are always best.

Given the multifactorial nature of FND, I tend to start therapy with a focus on the symptoms associated with the seizures, then work outward from there.

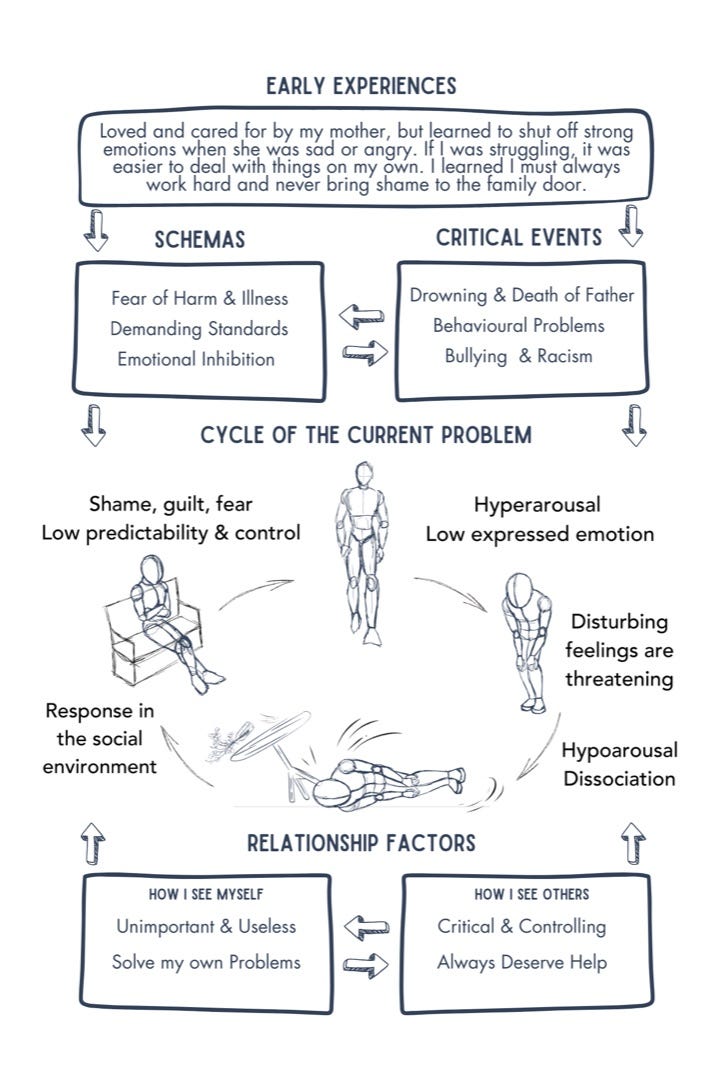

Below is an example from Nathan’s story that I introduced in Part One. Essentially, it depicts his subjective experience of childhood and adolescence, which contributed to the formation of “schemas” (cognitive, behavioural, and relational patterns) that, in part, influence the maintenance of his seizures.

Business as usual?

In my own practice, it’s common to hear people describe going numb in their bodies as soon as strong topics arise. No emotional exposure takes place if the person is cut off from feeling. This will be familiar to any therapist experienced in trauma work.

The main difference is that dissociation with non-epileptic attacks often comes in the form of a seizure. Sometimes these are brief or mild; other times they can last ten minutes or so. This may leave the person with extreme fatigue, memory gaps, or speech problems afterwards. Sometimes the client is completely wiped out for the rest of the session.

Essentially, managing dissociation is central to effective therapy, and it can take up much of the initial work. It can also be very frustrating for both clients and therapists, and requires patience and constant monitoring.

In-session techniques

There are many ways to manage dissociation; each therapist tends to pick up ways of working they are familiar with and trained in.

As an EMDR therapist, I tend to use tools I find work well for titration, particularly when trauma is part of the picture. Typically, I adapt Jim Knipe’s Constant Installation of Present Orientation and Safety (CIPOS) method.1 Rather than throwing someone in at the deep end, emotional exposure is approached in small, gradual steps, while consistently grounding them in present awareness.

This isn’t to push feelings away or sweep in prematurely, but to help the person stay online long enough for the body to register that difficult emotions can be tolerated. For some, that window can be very short indeed.

Mindfulness: the pros and cons

Mindfulness is a common go-to for many therapists and is a staple technique championed worldwide. In England, it’s commonly recommended by health professionals and large organisations such as the NHS, for a wide range of problems. While mindfulness can be helpful for some and shows evidence for preventing relapse in depression and for improving sleep quality, it can also have adverse effects.

For people who have experienced sexual trauma or other invasive experiences, observing thoughts without judgment can be very challenging.2 Focusing on breathing may trigger hyperventilation. For some, sitting quietly and noticing the body can feel so threatening that it provokes flashbacks or overwhelming sensations, leading to re-traumatisation.3

For people with dissociative seizures, mindfulness may potentially reduce seizure activity by lowering overall stress. But it can be common for people to be highly sensitive to changes in bodily sensations. Mindfulness can intensify this. In turn, an increased nervous system arousal can then trigger more seizures.4

In short, mindfulness is not something I recommend people practise on their own until I know them well and we have discussed both potential benefits and risks.

What about self-help?

By this point, I hope I’ve made enough of a case as to why self-help for dissociative seizures rarely goes beyond basic stress management. Unless symptoms are very mild and infrequent, most people need help from an experienced professional.

But some things can be done outside sessions to support the process.

Recording seizure frequency and intensity

One of the most useful things to do during therapy is to ask the client to keep a record of their seizure activity wherever possible. As I mentioned in last week’s post, change is rarely linear. I find it’s generally more productive to monitor the frequency and intensity of the seizures rather than trigger chasing.

Improvement can often be subtle and subjective, and keeping a daily record helps us to monitor whether things are improving, worsening, or staying the same.

Countering deconditioning

A common problem is increased anxiety about everyday tasks, such as using stairs, going out alone, and so on. Which is understandable, but can quickly lead to a loss of confidence and the person’s world can start to shrink. This gives room for depression to set in.

Physical deconditioning is also common, often linked to fatigue or other functional problems such as gait or movement issues. At times, this leads to the introduction and over-reliance on things such as walking aids, or wheelchairs.

In both cases, I encourage clients to use structured tools to start the process of reclaiming their life outside sessions, where possible. Here, I combine approaches from both physical management and mental health, adapted to the context of FND.

Creating an emotional map

Emotions manifest in specific areas of the body, but we often don’t notice them.

Guilt typically feels heavy in the chest, pressure in the throat and a slumped posture. Grief can feel similar, but with thoughts centred on loss. Fear often comes with a racing heart, shallow breathing, light-headedness, and a sense of needing to escape. Anger tends to be felt as heat rising in the body from the hips, accompanied by jaw tension and clenched fists. Shame may feel like a sinking sensation in the stomach, a flushed neck and cheeks, and a strong urge to run away and hide.

Mapping is about paying more attention to the body and using the information to build awareness. This way, the person can begin to identify the implicit triggers most closely linked to seizures in different contexts. It can also highlight patterns in terms of the surge of feelings around how significant others may respond to the seizures.

Exposure with pacing

Fatigue is super common. For some it can be constantly in the background, and it almost always follows an attack. Many people fall into a boom-and-bust pattern. On better days they push to catch up, then crash for days, then push again, and so on.

Pacing starts with a realistic baseline of activity that can be sustained. That might be a short walk, a set amount of household tasks, or a fixed number of work or study minutes, with brief periods of planned rest.

After establishing a manageable baseline, activity can increase in small steps. Sounds simple, but it is usually the hardest and most frustrating technique for clients to implement. There can be so many things that most people take for granted that can really burn through someone’s available energy: intense conversations, screen time, and being an emotional support for others; it all takes energy.

While pacing focuses on sustainable energy, graded exposure targets activities that are avoided due to anxiety. Combining pacing with exposure manages energy while reintroducing feared activities. It increases demand in the short term but reduces it in the long run.

The importance of “safety behaviour”

A key challenge in tackling anxiety-based avoidance is distinguishing genuine safety measures from safety behaviours. Safety behaviours are actions we use to reduce fear or discomfort. They rarely add real safety. More often, they erode confidence and reinforce the belief we can’t cope without them, which maintains avoidance.

Classic examples are objects or rituals perceived as preventing attacks: unopened bottles of water, foil-wrapped diazepam, menthol balm, lavender oil. Don’t get me wrong, swallowing diazepam would probably knock anxiety firmly on the head, but at the cost of dependence and other problems, which is why it isn’t prescribed long-term. But sealed in a packet in your handbag? Arguably that’s doing absolutely nothing to your nervous system.

The same goes for rubbing mint oil into your temples or taking big sniffs of potpourri. It may distract your senses momentarily, but it won’t touch the surge of adrenaline flooding your system when you’re sitting on the bus, worried you’ll black out.

People typically adopt safety behaviours either “just in case” or because they’ve falsely associated the object or ritual with quick relief. Unfortunately, the only way of tackling anxiety over the long-term is to face the fear, in a graded and sustained way.

Done consistently, this can bring lasting relief. It may also save you money on “anxiety-busting” potions and gadgets that, unless they cross the blood–brain barrier, are likely to have a placebo effect.

Why give credit to the mint balm when it’s you who worked hard to get on the bus in the first place?

The deal with too many safety nets

Avoidance doesn’t just apply to symptoms of anxiety. It can also influence bigger life choices. People may stay in jobs, avoid promotions, hold back from new hobbies or relationships. Sometimes there are practical reasons, but often it comes from fear of change, low confidence, or simply not having the energy to face it.

Identifying safety behaviours

Distinguishing safety behaviours from genuine safety can be tricky, especially with unpredictable seizures. It’s also important to focus on activities that are meaningful to you. Ask yourself:

Does this action objectively protect me from harm?

Is it based on fear or necessity?

Is the feared prediction likely to come true?

Does avoiding the activity limit independence?

Taking action

It helps to follow the four principles of graded exposure when reintroducing activities. For those with dissociative seizures and fatigue, it’s vital to factor in energy. That may mean adjusting other tasks on exposure days. Establishing your baseline through pacing first is usually the best approach. In some cases, the exposure task may need to be done more spontaneously if fatigue is very unpredictable.

Graded: Start with the least anxiety-provoking activity and master it before moving up.

Prolonged: Stay with the activity until your anxiety begins to drop.

Without distraction: Try not to rely on safety behaviours or thought-blocking. These erode confidence.

Repeated: Repeat until the activity no longer provokes high anxiety. The first attempts may feel intense and drain energy, but with repetition, anxiety reduces.

Seeking support with risk assessment

When challenging safety behaviours, it’s important to do so in a way that feels safe and manageable. Injuries are common with non-epileptic attacks, but everyone’s risks and circumstances differ. If you have other health conditions or disabilities, check with your healthcare professionals first. It can also help to discuss plans with a trusted friend or family member.

Learning to notice dissociation early

One technique I teach early in sessions, which can also be practised at home, is an adapted version of the “back of the head” exercise, used to monitor dissociation in EMDR.

Sit with your arm outstretched. Imagine a line running from your hand to the back of your head. Another option, if others are present, is to focus on an object or person in the room.

How present are you?

In the room"? Semi-present? Or somewhere else at the back of the head?

And finally… belly breathing

I know, I know. I can almost sense the eye-rolling.

Most of us have been told at some point to focus on our breathing when stressed. Whether you’re in a GP appointment with worrying symptoms, or you’ve just lost your job and your house is about to be repossessed, there’s always a breathing technique on offer. It’s not a cure-all. But there’s a reason it’s a staple tool in trauma therapy.

If you’ve ever watched a baby sleeping, you’ll notice they breathe from the stomach. This is natural breathing, which maintains gas exchange, supplies oxygen to the brain, and regulates heart rate. Many adults, under chronic stress, fall into the habit of shallow chest breathing. This can also cause something called “air hunger”, where we feel unable to get a full breath. Slowing our breathing down and breathing only from the stomach starts to reduce our heart rate and improve regulation.

It all sounds a lot, doesn’t it?

The bottom line is that managing dissociative seizures means working with a lot of moving parts. In my experience, keeping things structured, tangible, and as simple as possible goes a long way beyond getting caught up in theory or diagnosis.

Collaborative formulation and aims, pacing, exposure, and managing dissociation are key. None of it is quick or easy, but improvement in the seizures is possible.

That brings this three-part series to a close. From now on, I’ll be moving between long-form clinical posts and slightly shorter, more personal pieces in Unedited—a new section of the newsletter that explores a range of issues, including social media hype and the use and misuse of psychological concepts.

It would be great to hear from people in the comments. Whether positive feedback or a considered critique. You can use an emoji if you're unsure what to write.

It would be good to connect and break the echo chamber either way.

James :)

Knipe, J. (2018). EMDR Toolbox: Theory and Treatment of Complex PTSD and Dissociation (2nd ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Murray-Swank, N. A., & Waelde, L. C. (2013). Spirituality, religion, and sexual trauma: Integrating research, theory, and clinical practice. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

Godena, E., Saxena, A., & Maggio, J. (2020). Towards an outpatient model of care for motor functional neurological disorders: A neuropsychiatric perspective. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment.

Markus Reuber, M. D., Rawlings, G., & Schachter, S. C. (Eds.). (2018). In our words: personal accounts of living with non-epileptic seizures. Oxford University Press.